AAMVA Standards: How PDF417 Dominates Driver’s Licenses

The Role of AAMVA Standards in Barcode Scanning Applications

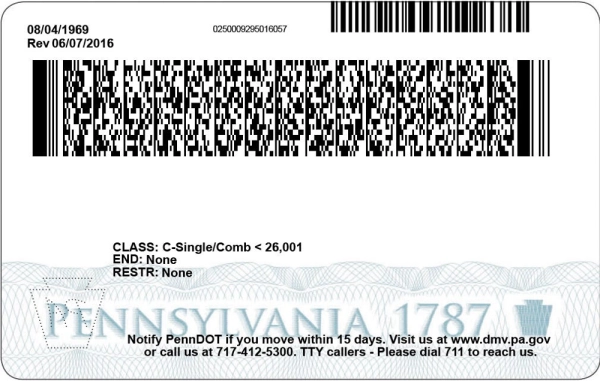

The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) has set influential standards for barcodes used on identification documents, especially driver’s licenses and state IDs. These standards specify using a PDF417 two-dimensional barcode on the back of ID cards to encode personal data in a uniform way. AAMVA’s barcode guidelines ensure that IDs issued by different jurisdictions (states, provinces, etc.) can be read and interpreted consistently. This report provides a deep dive into AAMVA’s barcode standards and their role in scanning applications. We compare AAMVA’s PDF417-based approach with other barcode formats like QR codes and Code 128, examine practical use cases across various industries, outline technical specifications and implementation details, and discuss the advantages, limitations, and adoption trends of AAMVA barcode standards.

AAMVA vs. Other Barcode Standards (PDF417, QR, Code 128)

AAMVA’s barcode standard is centered on the PDF417 symbology, which is a stacked linear 2D barcode format. It was chosen for its capacity to store substantial data and its error correction features. In practice, “AAMVA-compliant barcodes” usually refer to PDF417 codes formatted according to AAMVA’s data standard on IDs. To understand its role, it’s useful to compare PDF417 and AAMVA’s use of it with other common barcode types: QR codes and Code 128.

- PDF417 (AAMVA Standard): PDF417 is a 2D stacked barcode (appears as multiple lines of code stacked vertically) that can hold around 1100 bytes (over one kilobyte) of data. It encodes data in codewords across rows and includes robust Reed-Solomon error correction – up to ~50% of the code can be damaged and still recover data. PDF417 barcodes are rectangular and read by 2D imagers or even standard laser scanners (by sweeping across the code’s rows). AAMVA mandates PDF417 for driver’s licenses, leveraging its capacity to store all required personal identification info in one scan.

- QR Codes: QR codes are a 2D matrix barcode with a square grid pattern. They typically have higher data capacity than PDF417 (up to 2,953 bytes or over 7,000 digits) and are very fault-tolerant (30%+ error recovery). QR codes are widely used in consumer applications (marketing, mobile payments, website links) due to fast readability by phone cameras. However, QR codes are not commonly used on driver’s licenses in North America. One reason is size and format: a QR code encoding all ID data would take a larger printed area than a PDF417, and QR’s square shape can be harder to fit on a card design. Also, AAMVA’s established infrastructure and standards already revolve around PDF417. In short, QR codes excel in general-purpose use and higher capacity, but for IDs, PDF417’s long-form layout was preferred for compatibility with legacy 1D scanners and existing systems.

- Code 128: Code 128 is a 1D linear barcode (a single series of vertical bars) often used for product SKUs, shipping labels, and short strings of data. It can encode letters and numbers but has far lower data capacity – effectively a few dozen characters per barcode (its density is ~24 characters per inch). Unlike PDF417 and QR, Code 128 has no built-in error correction (aside from a checksum), meaning any damage can make it unreadable. Its advantage is simplicity: it can be scanned by any basic laser barcode scanner (no imaging needed), and it’s compact for small data. However, Code 128 cannot practically fit all the data required on a driver’s license (which includes name, address, dates, etc.). AAMVA did not choose Code 128 for IDs because it couldn’t meet the data storage needs and security (lack of error correction and data capacity) for modern licenses.

In summary, AAMVA’s PDF417 standard strikes a balance between data capacity and real-world readability. QR codes offer even more capacity and are great for marketing and mobile scanning, but they haven’t been adopted for driver’s license standards. Code 128 is ideal for simpler applications like retail products but is insufficient for the complex data on an ID card. The AAMVA PDF417 barcode remains the de facto choice for North American motor vehicle agencies, enabling a single-scan solution to retrieve a citizen’s identity data securely.

Practical Use Cases Across Industries

Because AAMVA-compliant PDF417 barcodes encode rich identity information in a standardized way, they have been embraced in multiple industries for a variety of applications.

Transportation and Travel

PDF417 barcodes appear not only on driver’s licenses but also on boarding passes and travel documents. Airlines often use PDF417 on boarding passes to encode the passenger’s name, flight number, and itinerary in a compact form. This allows quick scans at gates and security checkpoints. In the shipping and logistics sector, PDF417 labels are used on packages (for example by FedEx) to store tracking numbers and shipment details. Transportation agencies also use driver’s license scanning for identity verification – for instance, renting a car or verifying a truck driver’s credentials at weigh stations by scanning the license’s barcode.

Identification and Security

The primary use case of AAMVA barcodes is on driver’s licenses and ID cards for identity verification. Law enforcement officers use handheld or in-vehicle scanners to read the PDF417 on a license during traffic stops. This populates citation forms and checks databases instantly, improving efficiency and accuracy in issuing tickets or checking for violations. Security personnel at government buildings or controlled facilities also scan ID barcodes to log visitors or verify credentials. In access control, scanning an AAMVA-compliant ID can grant or deny entry based on the encoded data (e.g., verifying someone’s identity against a whitelist). The military and other institutions have adopted similar PDF417 barcodes on IDs for quick authentication and record-keeping.

Retail and Age-Restricted Sales

Many retailers leverage AAMVA barcodes to automate age verification for alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, or lottery sales. Instead of manually checking birthdates, clerks or self-service machines can scan the back of a customer’s ID to instantly read the date of birth (the DBB field) and determine if the customer is of age. For example, the Texas Lottery introduced vending machines that require scanning an ID’s PDF417 barcode to verify age before allowing ticket purchases. This process is facilitated by AAMVA’s standardized data, ensuring that the machine can interpret IDs from any state. Similarly, convenience stores and supermarkets use scanners at self-checkout; when purchasing alcohol, the system might prompt the customer to scan their driver’s license, automatically validating age with no room for clerical error. Retailers benefit from faster customer processing and reduced liability by consistently enforcing age rules.

Hospitality and Travel

Hotels may scan a guest’s driver’s license barcode at check-in to quickly capture name and address information into their system. Bars and nightclubs often use ID scanners at the door to verify age and even detect fake IDs. Because AAMVA barcodes contain multiple security features and data fields (like expiration date, DBA, and document number, DCF), some scanning software can flag IDs that don’t conform to known patterns (potential fakes). Car rental agencies similarly scan licenses to auto-fill customer data and check driving eligibility. In airlines and border security, while passports use a different standard (MRZ and chips), domestic travel ID checks (e.g., TSA checking a U.S. driver’s license) can be expedited by scanning the barcode to confirm the traveler’s identity and flight details.

Healthcare and Education

Hospitals sometimes use driver’s license scanning to quickly input patient information during admissions. Because the license barcode has the person’s name, birth date, and address, it can populate electronic forms and ensure accurate record matching. Pharmacies might scan ID barcodes to record who picked up a controlled prescription, automatically attaching the customer’s ID info to the transaction log. Some universities or exam centers accept driver’s licenses for check-in; an ID scanner can speed up logging students or examinees as they arrive by reading the barcode, rather than writing down details by hand.

These use cases demonstrate the versatility of AAMVA’s PDF417 standard beyond just driving credentials. Any industry that needs reliable identification or quick data capture can leverage the standardized barcode on IDs for efficiency and accuracy. By using a common format, interoperability is achieved – a law enforcement scanner, a retailer’s age-verification system, and an airline gate reader can all decode the same driver’s license data format and get the needed fields (Driver's License Barcode Reader - barKoder SDK).

Technical Specifications and Implementation of AAMVA Barcodes

AAMVA barcodes follow a well-defined data format and technical structure, particularly outlined in the AAMVA DL/ID Card Design Standard (latest revision 2020). Here we break down the key technical details of how these barcodes are formatted and implemented on ID cards:

- Symbology: The barcode is a PDF417 2D barcode symbol, printed typically on the back of the ID card. PDF417 is chosen as the mandatory machine-readable technology for AAMVA-compliant IDs (IDataCode - AAMVA PDF417 barcode generator.). It requires a higher-resolution printing process than a 1D barcode due to the dense stacked modules. The symbol can vary in size; standards usually define an X-dimension (module width) and Y-dimension (row height) that printers should use to ensure scannability. For example, Florida’s spec suggests an X of 0.0067 inch and Y of 0.02 inch for their PDF417 on licenses. This ensures the barcode fits in a roughly wallet-sized space and can be read by common scanners.

Data Encoding and Format: The data within the PDF417 is structured according to AAMVA’s Data Format standard (often called AAMVA PDF417 data spec or Annex D of the standard). The encoded string begins with a header that identifies it as an AAMVA file. A typical raw scan of a driver’s license PDF417 starts with:

@nu001erANSIfollowed by a six-digit Issuer Identification Number (IIN) and version codes. For example:@nu001erANSI 6360########DL#####...Here,

ANSI 6360...indicates the issuer (6360 for a particular jurisdiction), the AAMVA version number of the format, and the jurisdiction-specific version number. After the header, the data is divided into subfiles. The main subfile type isDL(for Driver License data). Additional subfiles (likeZVor others) can store jurisdiction-specific or optional info (e.g., vehicle registration info or other data).Data Elements: Within the

DLsubfile, information is stored in element fields identified by three-letter codes. Each field is either fixed or variable length as defined by the standard. For example:DCS= Last Name (Customer Family Name)DAC= First Name (Customer Given Name)DAD= Middle Name(s)DBB= Date of Birth (in YYYYMMDD format)DBA= License Expiration Date (YYYYMMDD)DBC= Gender (1 = Male, 2 = Female, etc.)DAQ= Driver’s License NumberDAG= Address Street- … and so on, as defined by AAMVA.

The standard mandates certain mandatory fields (like names, dates, license number, etc.) to always be present for compliance. Optional or jurisdiction-specific fields can also be included – for instance, some states add

DCF(Document Discriminator, a unique document ID) orDCG(Country) and use additional codes for organ donor status or veteran indicators. Each field in the barcode is typically terminated by a control character (like a line feed- Implementation and Parsing: Reading an AAMVA barcode requires two steps: first, decode the PDF417 image into the raw text string, and second, parse the string according to the spec to map the field codes to meaningful data. Many software libraries (and open-source projects) exist to parse AAMVA strings, given the complexity. For instance, the

IdParserandaamva_barcode_libraryin GitHub provide functionality to take a raw string from a scanner and output a structured data object (with keys likefirst_name,last_name, etc.). The parser must handle different AAMVA version years (e.g., 2000, 2005, 2020 standards had slight differences), and any custom fields a state might include in the "optional" data section. The header of the barcode indicates the version and number of data elements, helping the parser know how to interpret the rest. - Security Features: The AAMVA standard itself does not mandate encryption of the barcode data – most of the personal data is stored in plaintext in the PDF417 (IDataCode - AAMVA PDF417 barcode generator.). This is why scanning an ID instantly reveals all the printed info (and more) on the card. However, the standard does allow jurisdictions to encrypt certain data or include digital signatures in a separate subfile for authenticity (IDataCode - AAMVA PDF417 barcode generator.). Some newer implementations might include a hashed or signed portion of data (for example, to detect if an ID’s data was tampered with). Additionally, the AAMVA standard ties into ISO/IEC 15438 (PDF417 barcode standard) and other ANSI standards to ensure consistent encoding (using ASCII and ISO 8859-1 character sets for data, etc.). In practice, this means any compliant scanner should be able to decode the bits and get the correct characters for all fields (including international characters if used).

Implementing AAMVA barcodes on new IDs involves following these specs precisely. Each motor vehicle agency typically uses a software system that takes a person’s data and formats it into the AAMVA string, then prints the PDF417 on the card. On the scanning side, companies integrate AAMVA parsing into their systems, so the scanned data is correctly interpreted. The interoperability is such that a license from, say, California can be scanned by a police officer’s device in New York or by a bank’s account opening app in Florida, and the software will uniformly extract the person’s name, DOB, etc., thanks to the common AAMVA schema.

Advantages of AAMVA Barcode Standards

Using AAMVA’s PDF417 standards for barcode scanning on IDs offers several significant advantages.

Interoperability and Standardization

AAMVA’s standards ensure that all member jurisdictions (most U.S. states and Canadian provinces, for example) issue IDs with a common barcode format and data layout. This uniformity means a single scanner or software solution can handle IDs from multiple states without custom coding for each. It streamlines processes for federal agencies, airlines, retailers, or any business that deals with out-of-state IDs regularly. It also reduces errors – the field codes (DCS, DAC, etc.) mean the scanner knows exactly where to find the date of birth, the expiration date, and so on for any compliant ID (Driver's License Barcode Reader - barKoder SDK).

Rich Data Capacity

PDF417 can hold far more data than a magnetic stripe or 1D barcode. This allows comprehensive information (name, multiple addresses lines, physical descriptors, license classifications, etc.) to be encoded. For example, a PDF417 on a driver’s license can even include multiple subfiles – one for the main ID info and another for optional info like veteran status or even a biometric pointer. All this data is available from one quick scan, which is invaluable for law enforcement or forms processing. It’s effectively a portable data file (as the name implies), carrying a person’s identity data with them in machine-readable form.

Fast and Accurate Scanning

Automating data capture by scanning the barcode greatly reduces manual data entry. This improves speed – e.g., police issuing e-citations can shave minutes off each traffic stop by scanning rather than typing. It also improves accuracy, as it eliminates typos (no more mis-typed license numbers or misspelled names). In customer-facing scenarios, scanning an ID to auto-fill a form (at a bank or a rental counter) enhances user experience. AAMVA barcodes are designed to be read reliably; even if a card is a bit scratched or worn, the error correction in PDF417 often still lets the data be recovered.

Enhanced Security and Verification

While the data on the barcode is often not encrypted, using a barcode itself adds a layer of security: it’s harder to alter than printed text. If someone tried to paste a new photo on an ID or alter the printed date of birth, the barcode data (which they likely cannot easily rewrite without specialized tools) would reveal the true info. Many systems cross-check the printed info with the barcode info; a mismatch can indicate tampering or a fake ID. Additionally, because the barcode can include things like a digital signature or document discriminator, it helps detect counterfeits (a random fake ID might have a barcode number that doesn’t match any real issued ID, or fails a checksum). Security is also improved by reducing human error – verifying age or identity via automated lookup is more consistent than a visual check by staff that might be hurried or inattentive (Driver's License Barcode Reader - barKoder SDK).

Broad Industry Support

The AAMVA standard’s prevalence means that a broad ecosystem of hardware and software supports it. From DMV issuance systems to off-the-shelf ID scanners, the market has standardized on PDF417 for IDs in North America. This drives costs down for equipment (as it's widely produced) and makes training easier (users become familiar with the same process everywhere). New applications can readily leverage existing SDKs or APIs to implement ID scanning, benefiting from years of refinement in those libraries.

Resilience

PDF417’s robust error correction (up to 50% damage recoverable) means the barcodes remain readable even after some wear and tear. This is crucial since driver’s licenses are carried daily and can get scratched or scuffed. AAMVA’s guidelines for print quality ensure that even if one part of the code is scratched, redundancy in the code often still allows data to be extracted. In contrast, a magstripe (previous tech on IDs) can be rendered completely unreadable by one bad scratch across the strip.

Limitations and Considerations

Despite its many advantages, the AAMVA barcode standard and PDF417 technology have some limitations and considerations to keep in mind. Let's have a look into some of them.

Specialized Scanning Equipment

Reading a PDF417 barcode requires either an imaging scanner or a laser scanner capable of 2D barcode reading. Traditional 1D laser scanners (like those used for UPCs in older retail settings) cannot interpret PDF417 in one pass. While 2D imaging cameras have become common (even smartphone cameras can do the job), there is still a need for proper software to decode and parse the data. For some small businesses or agencies, upgrading scanners to read PDF417 was a barrier during the transition from magnetic stripes to barcodes. However, this is less of an issue today as 2D scanners are widely available.

Privacy Concerns

Because the AAMVA barcode often contains unencrypted personal information, anyone with a 2D scanner can potentially read all the data on a lost or stolen ID. There have been concerns about oversharing: for example, when a clerk scans your license to verify age, they might inadvertently capture your address, license number, and other details which they don’t actually need for that purpose. This has raised calls for data minimization – some jurisdictions or businesses have policies to parse only certain fields and ignore others to protect privacy. Nonetheless, the onus is on the implementer to handle the data carefully, since the barcode will give everything by default. In the Texas Lottery example, officials clarified that the vending machine scanners do not store any ID data; they just check the date of birth and discard the rest. Organizations must ensure compliance with privacy laws when using ID scan data.

Data Updates and Versioning

The AAMVA standard has evolved (versions in 2000, 2003, 2005, 2009, 2016, 2020, etc.), adding new fields or changing some definitions. Not all states immediately adopt the latest version; some might use an older version format for years. This can complicate parsers – they need to handle multiple versions. For instance, an older license might not have some of the newer field codes. Also, some states include non-standard fields in the “optional” section, which might not be documented publicly (for security or simply because they’re local use). If a scanner isn’t updated to recognize those, it might output raw or confusing data. The good news is the AAMVA header includes the version number and a field count, so a well-designed parser can adapt logic based on that. Still, this requires maintenance as standards evolve.

Physical Size and Aesthetics

PDF417 barcodes, while compact for the data they carry, are relatively large on a card. They occupy a significant portion of the back of a driver’s license. This leaves less room for other features (like additional security holograms or graphics). It’s a trade-off: a QR code might store the same data in a smaller area (because it’s 2D matrix, it can be denser), but QR codes weren’t chosen likely due to other reasons as mentioned. For very small form-factor IDs or documents, PDF417 might be too large; in such cases, other tech like magnetic stripes (historically) or smartchips/NFC (as in biometric passports or e-ID cards) might be used to supplement or replace it.

Not Human-Readable

If the barcode is damaged beyond readability, the information it held might be lost unless it’s also printed on the card. AAMVA standards ensure critical info is also printed in text on the front of the ID, so the barcode is supplementary from a human perspective. However, some non-obvious data (like the document discriminator or inventory control number) might only be in the barcode. If a jurisdiction relied on the barcode for something and it fails, there’s no manual fallback for that particular piece of data. In practice, this is a minor issue since most key data is visible on the card and barcode failure would just require manual entry of that data.

Security (Forgery)

While the barcode makes casual forgery harder (because replicating a valid barcode with proper data is non-trivial without specialized knowledge), sophisticated counterfeiters have, in some cases, created fake IDs with barcodes that do scan. They might use an ID template generator to encode false data that matches the fake printed info. Basic scanners will accept it as long as the format is correct. To counter this, some states encrypt parts of the data or include digital signatures that are hard to clone without the private keys. If a verifying system doesn’t check for those, it could be fooled by a well-crafted fake. Thus, while AAMVA barcodes improve security overall, they are not foolproof – they should be one layer of a multi-layered ID verification approach (with holograms, UV features, database checks for the ID number, etc., providing additional validation).

Adoption Trends and Industry Applications

Adoption of AAMVA’s barcode standards has been widespread across North America since the late 1990s and has only grown.

Driver’s License Issuing

Nearly all U.S. states and Canadian provinces have adopted the AAMVA PDF417 barcode on their driver’s licenses and ID cards. In the early years, some states still used magnetic stripes or even 1D barcodes, but over time PDF417 became the norm because of AAMVA’s guidance and the push for uniformity. By the 2010s, it was standard for new license designs to include the PDF417. Some states have even removed the magnetic stripe (relying solely on the 2D barcode) in newer designs, signaling confidence in the barcode technology. According to AAMVA, the goal was interoperability and improved security, which has largely been achieved across jurisdictions. The adoption is not limited to the U.S. – for instance, Mexico uses PDF417 on its national ID cards and some licenses, and Canadian provinces do as well, aligning with the same standards.

Beyond North America

AAMVA’s influence has extended internationally. South Africa notably adopted PDF417 barcodes on its driver’s licenses and vehicle registration discs, inspired in part by the success in North America. Their barcodes are similarly dense (holding hundreds of bytes, including a driver’s photo and fingerprint data in compressed form). While South Africa’s implementation is not exactly the same data format as AAMVA, it shows the trend of using PDF417 for official ID documents. Other countries have also used PDF417 for certain identification purposes (though Europe, for instance, went more towards smart chips for their driver’s licenses). Still, the concept of a machine-readable zone on an ID is now common worldwide, whether it’s a PDF417, QR, or MRZ. AAMVA continues to work with ISO to possibly influence international standards (ISO 18013 for Driving License), ensuring some level of compatibility globally.

Retail and Commercial Use

Many industries have integrated AAMVA scanning into their standard operating procedures. Airlines and TSA use it for ID verification at airports: when you show your driver’s license, the agent may scan it with a device that reads the PDF417 and instantly pulls up the info to cross-verify with your boarding pass and their security database. Bars and nightclubs widely use ID scanning devices at entry – these not only check age but often log the ID (to ban troublemakers, or just keep a count). The tech behind almost all these systems is reading AAMVA barcodes. There’s been growing adoption in the hospitality sector as well – for instance, casinos scan IDs to enroll patrons in loyalty programs or check self-exclusion lists, leveraging the standard format to integrate with their databases. In healthcare, some e-prescription systems require pharmacists to scan the patient’s ID to attach a verified ID record to certain drug purchases, which is made possible by the uniform data format.

Technology Evolution

As smartphone cameras and apps have improved, we see adoption of mobile scanning of AAMVA barcodes. Apps can now read a driver’s license barcode using the phone’s camera and parse it on-device. This has enabled things like digital identity verification for online services: for example, a banking app might ask the user to scan the barcode on their ID to auto-fill a sign-up form or to verify identity remotely. AAMVA’s standardized format makes it easier for such apps to be written – they know what fields to expect, so they can programmatically extract your name, address, and DOB once the barcode is decoded. This trend is growing, especially as remote onboarding and KYC (Know Your Customer) processes move to mobile.

Mobile Driver’s Licenses (mDLs)

The latest trend in ID is the mobile driver’s license, a digital credential stored on a smartphone. AAMVA has been involved in pilots and standards for mDL (which is being standardized in ISO 18013-5). While mDLs don’t use printed barcodes, the existence of the AAMVA PDF417 standard helped underscore the importance of standard data formats. The new mobile IDs aim to convey the same information in a secure digital way (often via QR codes generated on screen, or NFC transmissions). Some states have started offering mDLs, but physical cards with PDF417 aren’t going away soon – they are a proven technology with decades of infrastructure. There may be a long period of dual use. The adoption of mDLs will be another area to watch, and AAMVA is ensuring that the data elements and trust frameworks line up with what’s on the physical ID, so systems remain compatible.

Continuous Improvements

Industry feedback has led to small adjustments, like truncation indicators for names (fields DDE, DDF, DDG tell if a name had to be cut off due to length). Adoption of those new fields addressed edge cases (so scanners don’t misinterpret a shortened name). There’s also been adoption of using the barcode for more than just person data: some states encode a digitized photo or signature as binary data in the barcode (though this can push the limits of size). Research into better compression or alternate 2D codes occasionally comes up, but so far PDF417 has remained the choice due to its installed base.

Cross-Industry Use

Outside of IDs, PDF417 (and by extension AAMVA’s usage of it) has found niche adoption in other areas. For example, courier services and the postal service use PDF417 on package labels for internal tracking. In some cases, these codes might even follow a similar idea of storing data records that can be parsed. The fact that AAMVA’s use proved PDF417 could handle mission-critical data has given confidence in using it for other applications like inventory management and ticketing.

In conclusion, AAMVA’s barcode standards built on PDF417 have achieved near-universal adoption in North American motor vehicle identification and have strongly influenced barcode scanning practices in many sectors. The trend is towards even greater integration – with technology making it easier to scan and use that data in real-time – and towards ensuring security and privacy keep pace with the convenience. The AAMVA PDF417 barcode has become a linchpin of modern ID verification, enabling everything from faster traffic stops to automated liquor sales checks, and its role is likely to persist even as new digital ID technologies emerge.

Final thoughts

AAMVA’s standards for barcode scanning – centered on the PDF417 2D barcode – have transformed how identification information is captured and used. By standardizing the data format and embracing a high-capacity, error-tolerant barcode, AAMVA enabled interoperable systems for driver verification, law enforcement, commerce, and more.

Notably, barKoder excels at scanning PDF417 barcodes and specifically the AAMVA format, we've put a lot of effort in improving the scanning capabilities of our SDK for these use cases as this is the most wide spread method that is used for personal data storing.

In comparing AAMVA’s PDF417 with alternatives like QR codes and Code 128, it’s clear that the chosen approach balances data needs with practicality in scanning technology. The use cases spanning transportation, retail, security, and others illustrate the broad impact of having a common, scannable ID format.

Technically, AAMVA barcodes pack a wealth of information in a structured way, and while they require careful parsing and attention to privacy, they vastly improve efficiency and accuracy wherever they are used. The advantages – from speed and reliability to enhanced security – generally outweigh the limitations. As adoption has grown, the ecosystem of scanners and software has matured, making AAMVA barcode scanning a staple in daily transactions and public safety operations. Looking ahead, these standards provide a foundation that will likely influence next-generation digital IDs, ensuring that trusted and quick machine-readable identification remains a cornerstone of modern society.