From Beeps to Understanding: The Evolution of the Barcode

The First Attempt

The barcode did not begin as a technology. It began as frustration.

In the years following World War II, American retail was changing faster than its tools could keep up. Supermarkets were growing larger, offering more products, and attracting more customers, but the systems that supported them remained stubbornly manual. Every item had to be price-marked by hand. Every price change meant hours of rework. At checkout, cashiers read labels, keyed numbers, and made mistakes. Inventory losses mounted quietly through human error and miscounts. The problem was obvious to anyone running a store, but no one knew how to solve it.

In 1948, that frustration found its way into an academic hallway. Samuel Friedland, an executive at the Food Fair supermarket chain, approached the dean of the Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia with a simple question: Could the university help invent a way to automatically read product information at checkout. The dean dismissed the idea, reportedly saying it was not part of the curriculum. But the conversation was overheard!

Bernard “Bob” Silver, a graduate student in electrical engineering, caught the question as it drifted past him. He immediately sensed that it was not just a retail problem, but an information problem.

Silver brought the idea to Norman Joseph Woodland, an instructor at Drexel with a background in mechanical engineering, physics, and industrial systems. Where Silver saw the opportunity, Woodland saw the challenge.

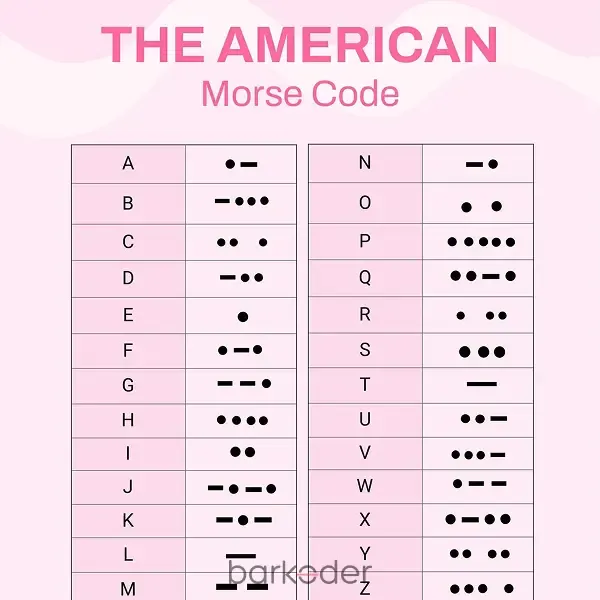

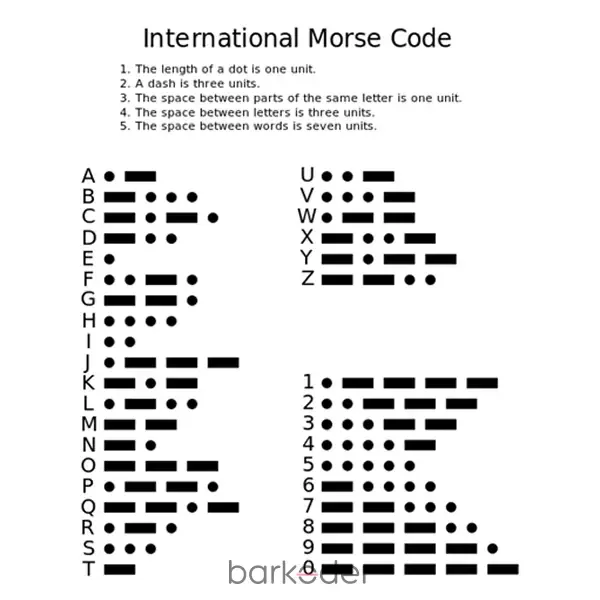

Woodland did not try to solve the problem at his desk. He quit his job and left Philadelphia, heading to Miami Beach to think. What he needed first was not a machine, but a way to represent information in a form that could survive the physical world. The breakthrough came from an unexpected place. Morse code.

Woodland had learned Morse code as a child in the Boy Scouts, where information was encoded not in symbols, but in timing. Short signals and long signals. Dots and dashes. Sitting on the beach, running his fingers through the sand, he realized that time could become space. A short signal could become a narrow line. A long signal could become a wide one. The pauses between signals could become white space. Information no longer had to exist in motion. It could be printed.

Years later, Woodland described the moment plainly. He dragged his fingers through the sand, looked down at the grooves, and understood that information could be encoded as lines. Wide and narrow. Black and white. That gesture, almost accidental, became the conceptual birth of the barcode.

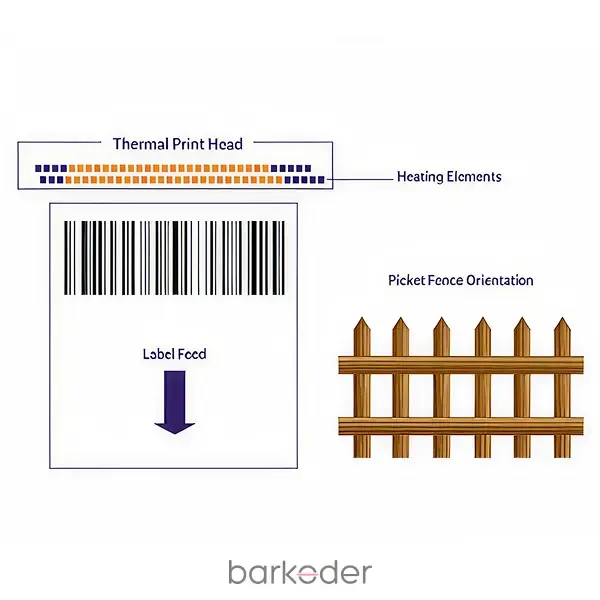

The first design was linear, a simple sequence of parallel lines that came to be known as the “picket fence.” It looked remarkably similar to the barcodes we recognize today. But Woodland quickly identified a fatal flaw. A linear code demanded precise orientation. For a single scanning beam to read it, the product had to be positioned just right. In a busy checkout lane, that requirement would slow everything down.

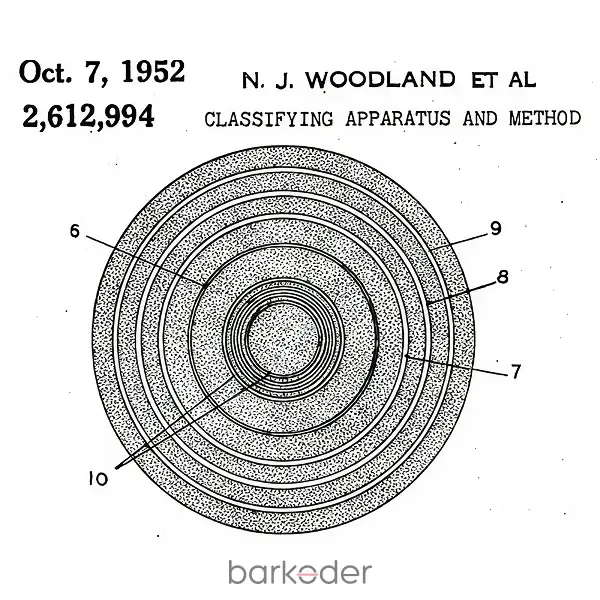

To solve this, Woodland did something radical. He wrapped the lines into concentric circles, creating what would later be known as the bullseye code. No matter how the product was rotated, a scanning beam would intersect the pattern somewhere. Orientation no longer mattered. Conceptually, it was elegant. Technically, it was ambitious.

The proposed scanning system relied on intense light sources and photodetectors. A powerful lamp would illuminate the code. Black rings would absorb the light. White spaces would reflect it. A photocell would translate those fluctuations back into electrical signals. In theory, it worked. In practice, it demanded hardware that simply did not exist yet.

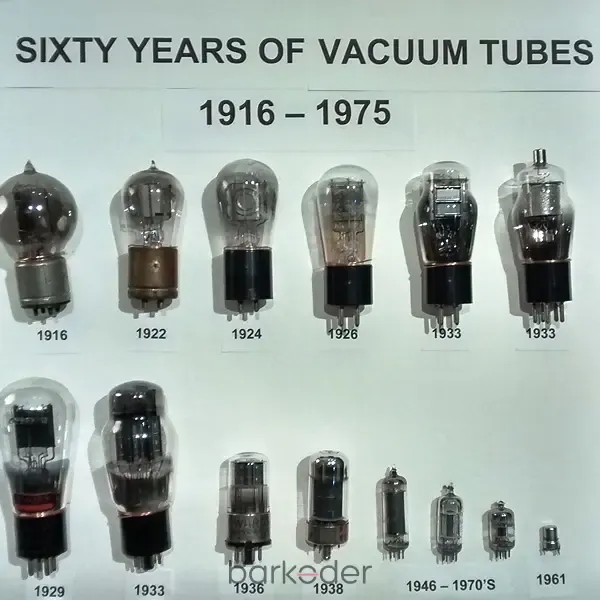

In 1949, Woodland and Silver filed a patent for their system. In 1952, it was granted as U.S. Patent 2,612,994, titled “Classifying Apparatus and Method.” The invention was real, but the world it required had not arrived. The light sources were inefficient and burned hot. The electronics relied on bulky vacuum tubes. A single checkout installation would have cost tens of thousands of dollars, an impossible expense for an industry built on thin margins.

That same year, the patent was sold to RCA for $15,000, a modest sum even by the standards of the time. Both inventors moved on. Bernard Silver would die of leukemia in 1963, never seeing the barcode succeed. Norman Joseph Woodland joined IBM, carrying with him the memory of an idea that had failed not because it was wrong, but because it had arrived too early.

The bullseye barcode solved the hardest conceptual problems. Encoding information. Handling orientation. Translating physical marks into data. What it lacked were the technologies that would one day make it practical. The laser and the microprocessor had not yet entered the story.

For the barcode, this was not an ending. It was a pause!

II. The Industrial Prelude: Trains and Lasers (1960s)

This era is often overlooked, but it is critical. Before the barcode could handle a pack of gum, it had to handle a 100-ton freight train moving at 60 miles per hour. This section explores the first major commercial attempt at automated identification: KarTrak.

While the grocery industry was stalling due to technological limitations, the American railroad industry was facing a logistics crisis. This shifted the barcode’s development from a consumer convenience project to a heavy industrial necessity.

The Problem: Lost in Transit

By the early 1960s, the North American rail network was vast and chaotic. Nearly 2 million freight cars moved across the continent, constantly being switched between different railroad companies—a Union Pacific car might be transferred onto a Santa Fe track, and vice versa.

Tracking these cars was entirely manual. Men known as "scouts" stood in rail yards writing down serial numbers of passing trains on clipboards. The error rate was high, and cars were frequently "lost," sitting idle in sidings for weeks because no one knew where they were. This inefficiency cost the industry millions in underutilized assets.

The Innovator: David Collins and the Birth of KarTrak

The solution to the railroad industry's tracking crisis came from an unexpected source: David Collins, a disciplined MIT graduate working at Sylvania (GTE).

Collins was familiar with the Woodland/Silver patent, but he immediately recognized a fundamental problem with applying their black and white bar concept to freight trains. A black bar printed on the side of a dark, dirty train car would simply disappear into the background, rendering the entire system useless. The solution couldn't rely on contrast between ink and surface; it needed to create its own light.

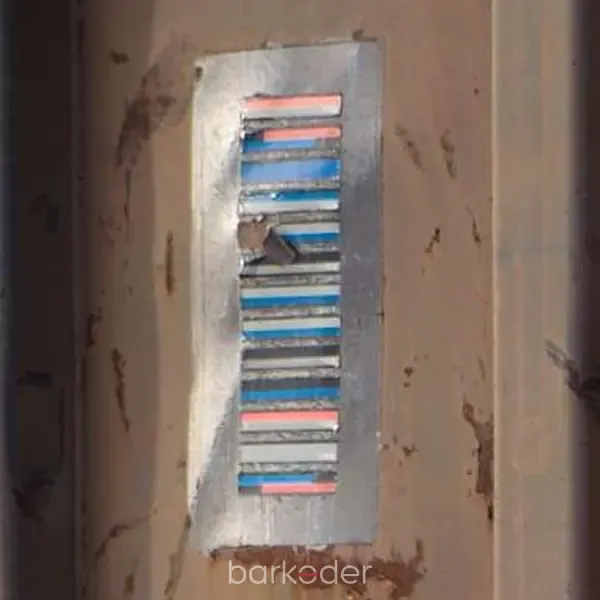

Collins's breakthrough was to abandon the passive ink on paper approach entirely and instead use retro-reflective tape, specifically Scotchlite by 3M, the same material that makes stop signs glow in headlights.

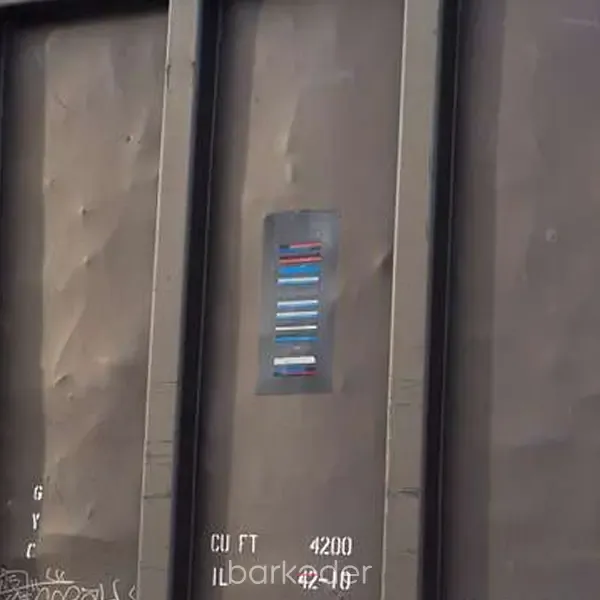

This material has a unique property: it bounces light directly back to its source, creating a brilliant reflection regardless of the surface color beneath it. Collins designed a system he called KarTrak, and it looked radically different from anything that would follow. Instead of a simple row of vertical bars, KarTrak used a "ladder" design: a stack of horizontal stripes in combinations of Orange, Blue, White, and later Black. Each color combination encoded specific numbers, allowing the system to identify both the owning railroad (such as "UP" for Union Pacific) and the individual car number.

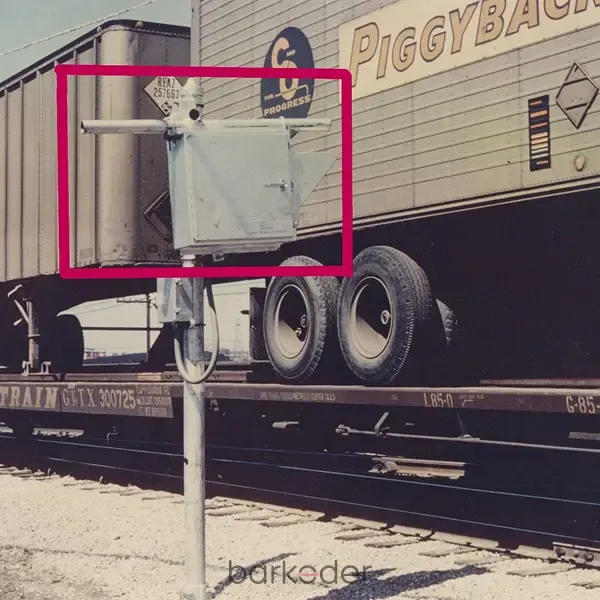

To read these codes, Sylvania built massive trackside scanners. The early versions used high intensity xenon lamps to illuminate the reflective strips, but the real breakthrough came when the system was upgraded to use a helium neon laser.

This laser technology, still in its infancy in the 1960s, allowed the scanner to read the reflective stripes from several feet away, even through rain, fog, or darkness, and most impressively, while the train was moving at full speed. For the first time, automatic identification wasn't just a laboratory curiosity; it was working in the brutal conditions of the real world.

The Rollout: ACI and the National Standard (1967)

The Association of American Railroads (AAR) saw the potential and moved aggressively. In 1967, they adopted KarTrak as the standard for Automatic Car Identification (ACI) and mandated that every freight car and locomotive in North America be tagged. This was a massive industrial undertaking, and by 1974, over 95% of the fleet was tagged with these colorful barcode ladders.

The Collapse: Why It Failed

Despite the successful rollout, the system was abandoned in the late 1970s. The failure was due to the harsh reality of the environment. The reflective properties of the Scotchlite tape were brilliant in a lab, but on the tracks, the labels quickly became coated in brake dust, mud, and diesel soot. Once the reflectivity was compromised, the scanners couldn't read them. Railroad companies, already struggling financially, didn't maintain the labels. A "no-read" meant the car had to be manually checked anyway, negating the system's value. The AAR officially abandoned the ACI system in 1977.

The Legacy: Lighting the Fuse

While KarTrak failed as a product, it succeeded as a proof of concept. It proved that optical scanning could capture data faster and more accurately than humans. Most importantly, it pushed the development of laser scanning technology. When the grocery industry looked at the problem again in the 1970s, the laser technology incubated by the railroads was ready to be adapted for the checkout counter.

Frustrated by Sylvania's lack of vision for other uses of the technology, David Collins quit and founded Computer Identics Corporation. In 1969, Computer Identics delivered the world's first commercial laser scanner to General Motors, where it was deployed on a Pontiac assembly line to automatically identify and track car components. Later that year, the company installed a more sophisticated system at a General Trading Company facility in Carlstadt, New Jersey. This system paired their scanners with a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 minicomputer to automatically sort grocery orders. As boxes moved along a conveyor belt, the scanner read their codes and diverted them to the correct loading dock. By 1971, Computer Identics had developed specialized package recognition scanners—the direct ancestors of the systems used by modern delivery companies like UPS and FedEx.

III. The Retail Revolution: The Battle for the Standard (1970–1973)

The Ad-Hoc Committee

This period is often described as the “Manhattan Project” of the grocery industry, and the comparison is not exaggerated. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, supermarkets were drowning in complexity. The average American grocery store had grown from roughly 3,000 items in the 1940s to more than 10,000, and that number was still climbing. Every new product meant more pricing labels, more inventory mistakes, more checkout delays. Profit margins had collapsed to a terrifying 1 percent, leaving no room for inefficiency. Automation was no longer a nice idea or a future investment, it had become a matter of survival.

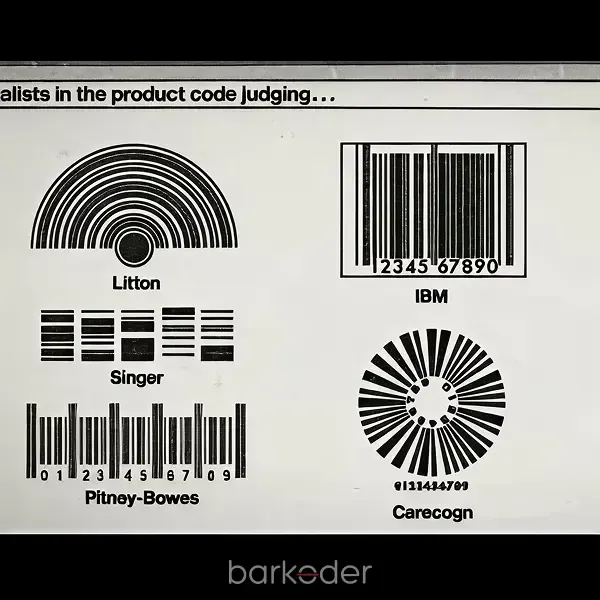

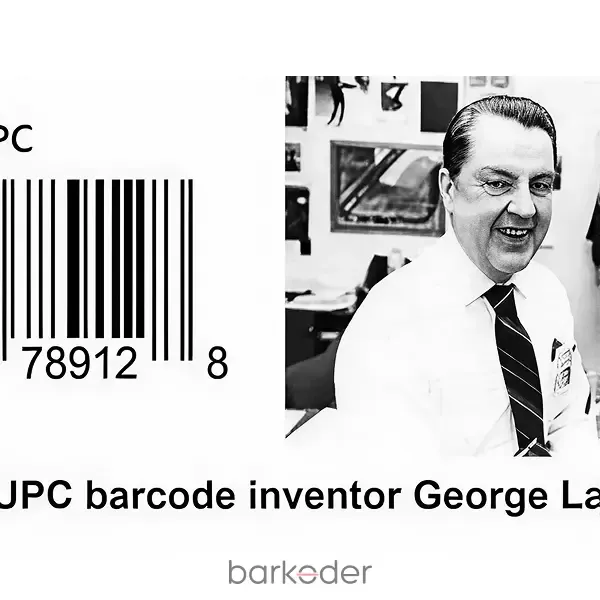

The industry quickly realized that no single retailer could solve this problem alone. In 1970, grocery executives came together to form what would become the Uniform Grocery Product Code Council, a rare moment of cooperation among fierce competitors. The goal was brutally simple and unforgiving. They needed to agree on one universal code, something every manufacturer would print and every retailer could read. If Heinz printed one symbol and Campbell’s printed another, the entire system would collapse before it even started. The effort was led by Alan Haberman, the CEO of First National Stores, a pragmatic and demanding executive who cut through theoretical discussions with a single requirement. He wanted a code that could be printed on a can of Coke and a bag of potato chips, two surfaces that could not have been more different. In 1971, the council issued a formal request for proposals, effectively inviting the world’s largest technology companies into a high-stakes competition. Companies like RCA, IBM, Singer, Litton, and Pitney Bowes all submitted designs, knowing that whoever won would shape the future of retail.

Obvious Frontrunner RCA

Early on, RCA emerged as the front-runner. They had a major advantage because they owned the original patent rights to Norman Joseph Woodland’s bullseye barcode, the circular design conceived decades earlier. RCA’s logic was elegant and intuitive. If cashiers needed to scan products quickly from any angle, then the code itself should be readable from any angle, and nothing achieved that better than a circle. In 1972, RCA installed bullseye scanners in a Kroger supermarket in Cincinnati, and at first the system felt almost magical. Customers watched in amazement as products were scanned instantly without manual price entry. It looked like the future had arrived.

Reality bites back

Then reality intervened in the most unglamorous way possible, through ink and paper. The problem became known as printing gain. In mass printing, ink naturally spreads slightly when it hits packaging material. On a traditional linear barcode, a slightly wider bar is usually tolerable because scanners can still interpret the pattern. But with concentric circles, even minor ink spread caused the rings to bleed into one another. The delicate ratios between black and white were distorted, and the data itself was corrupted. As more products were printed at scale, the RCA scanners began failing more frequently. Codes that looked perfectly fine to the human eye suddenly became unreadable to machines. What had seemed like the most elegant solution revealed itself as too fragile for the harsh realities of industrial printing.

IV. The IBM Intervention

Label type | Label dimensions | Area |

|---|---|---|

Bull's eye with Morse Code | Large | Large |

Bull's eye with Delta B | 12.0 in (300 mm) diameter | 113.10 in2 (729.7 cm2) |

Bull's eye with Delta A | 9.0 in (230 mm) diameter | 63.62 in2 (410.5 cm2) |

Baumeister 1st w/ Delta B | 6.0 in × 5.8 in (150 mm × 150 mm) | 34.80 in2 (224.5 cm2) |

Baumeister 2 halves w/ Delta B | 6.0 in × 3.0 in (152 mm × 76 mm) | 18.00 in2 (116.1 cm2) |

Baumeister 2 halves w/ Delta A | 4.5 in × 2.3 in (114 mm × 58 mm) | 10.35 in2 (66.8 cm2) |

Baumeister with Delta C | 1.5 in × 0.9 in (38 mm × 23 mm) | 1.35 in2 (8.7 cm2) |

The 12-Digit Architecture

The Decision: April 3, 1973

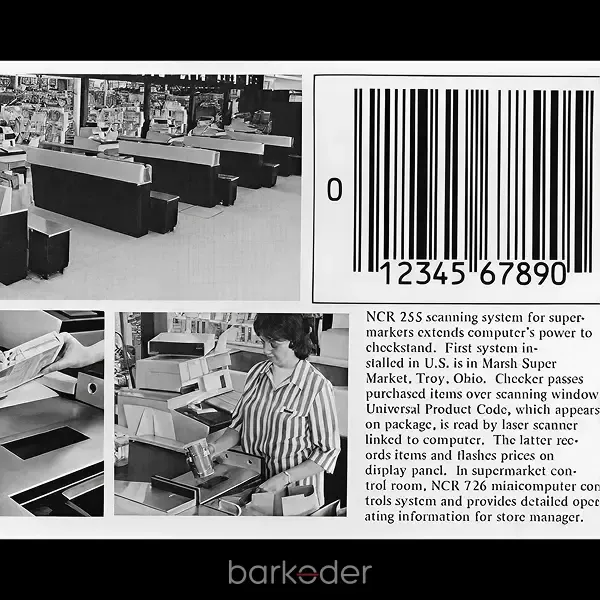

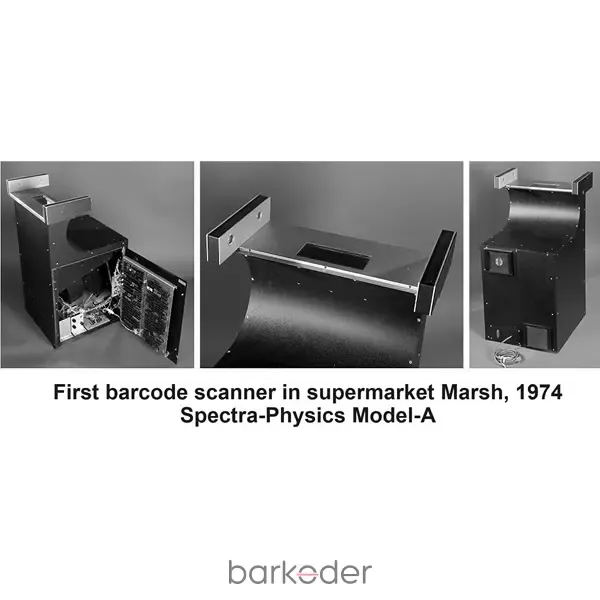

V. After the Vote: Resistance, Retrofitting, and the First Beep

A Standard Without Believers

A Proving Ground in Plain Sight

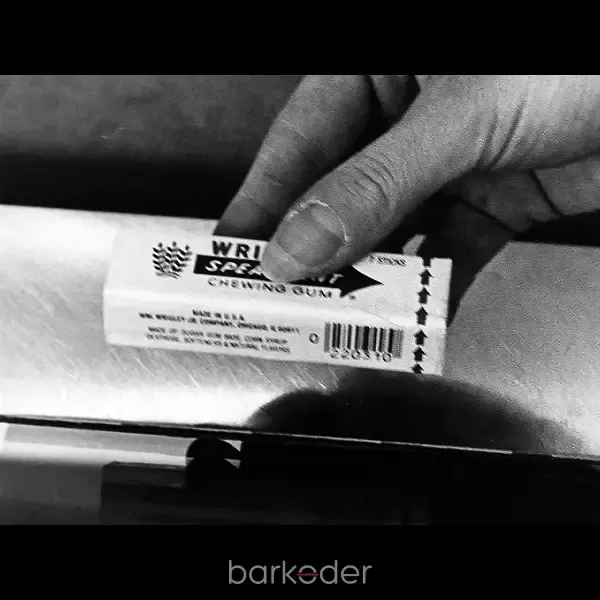

June 26, 1974

The Transaction That Proved the Hypothesis

The Stalemate

What the Scanner Really Changed

VI. Beyond the Grocery Store: The Explosion of Symbologies After 1980

One Success Was No Longer Enough!

By the early 1980s, the barcode had quietly crossed an invisible line. It was no longer an experiment, and it was no longer limited to grocery stores. The UPC had proven that machine-readable identification could work at scale, and once that truth settled in, other industries began asking a dangerous question. What if this idea did not have to stop at retail.

Same problem, Many Environments

The first realization was that one barcode could not serve every purpose. UPC was perfect for consumer goods sold at checkout, but warehouses, factories, hospitals, and shipping companies had very different needs. Some needed to encode more data. Others needed codes that could be printed smaller, scanned from farther away, or survive dirt, abrasion, and damage. What followed was not a replacement of UPC, but an expansion around it.

Stretching the Line: Linear Codes Beyond Retail

In Europe, retailers adopted EAN, a close relative of UPC that expanded the numbering system to support international manufacturers. In logistics and industrial environments, Code 39 and Interleaved 2 of 5 gained traction because they were flexible, easier to print, and could encode alphanumeric data. As computing power improved, more sophisticated symbologies emerged. Code 128 allowed dense encoding of large data sets in a compact space, making it ideal for shipping labels and internal tracking.

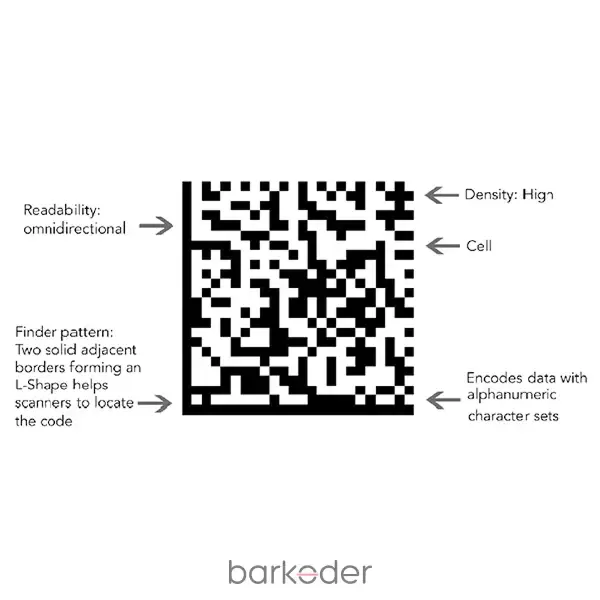

From Identifier to Container

The real shift came when engineers stopped thinking of barcodes as just price lookups and started treating them as data containers. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, two-dimensional codes entered the scene. Unlike linear barcodes, these symbols stored information both horizontally and vertically, dramatically increasing capacity. PDF417 found early use in transportation and identification documents. Data Matrix proved resilient even when printed extremely small or partially damaged, making it ideal for electronics and medical devices.

Speed, Resilience, and the Road Ahead

A few years later, QR codes would push the idea even further, designed for rapid scanning and error correction in industrial environments before eventually escaping into consumer life.

None of this replaced the original barcode. Instead, the ecosystem grew outward. UPC remained the backbone of retail, while new symbologies filled the gaps that UPC was never designed to handle. What emerged was not a single standard, but a family of standards, each shaped by the constraints of its environment.

By the end of the twentieth century, the barcode was no longer a grocery innovation. It was a universal language spoken differently in factories, warehouses, hospitals, airports, and eventually on smartphones. The bars themselves had multiplied, changed shape, and gained depth, but the core idea remained untouched. Encode reality in a way machines can trust, and entire systems reorganize around it.

VII. From Laser to Camera

The Limits of the Sweep

For nearly two decades, barcode scanning meant one thing. A laser swept across a surface, light reflected back, and a pattern of bars was translated into data. It was fast, precise, and brutally efficient, but it was also narrow in what it could understand. Laser scanners did not see symbols, they sampled them, one line at a time, assuming that all meaningful information lived along a single horizontal path.

That assumption held as long as barcodes remained linear. UPC, Code 39, and Code 128 were all designed around the strengths and limitations of laser scanning. Orientation mattered. Distance mattered. Curvature mattered. The symbol and the reader were locked together in a quiet agreement. As long as each respected the other’s constraints, the system worked!

But as barcodes spread beyond checkout lanes, that agreement began to break down. Warehouses demanded smaller labels. Manufacturers wanted to encode more information. Medical and electronics industries needed symbols that could survive damage, distortion, and tight spaces. The barcode evolved faster than the scanner built to read it.

Lasers began to show their limits not because they were inaccurate, but because they were blind to context. A laser could not understand a surface. It could not reason about perspective or reconstruct missing data. It could only report what passed under its beam. Reading more complex symbols required either mechanical complexity or multiple passes, both of which introduced fragility and cost.

When Optics Gave Way to Electronics

The first shift away from lasers was subtle. In the late 1990s, scanners began replacing moving laser assemblies with solid-state linear sensors, often CCD-based. These devices still read one line at a time, but they eliminated mechanical parts, reduced failure rates, and lowered costs. More importantly, they nudged scanning away from optics and toward electronics. The scanner was no longer interpreting reflected motion, it was processing captured data.

Seeing Instead of Sampling

The real break came when scanners stopped sampling lines altogether and started capturing images. With the introduction of area imagers, scanning crossed a conceptual boundary. Instead of reconstructing a symbol from motion, the device could now see the entire symbol at once. Orientation stopped being a requirement. Partial damage became recoverable. Perspective distortion could be corrected in software. Decoding shifted from hardware precision to algorithmic interpretation.

This change rewrote the rules. Once a scanner could capture an image, the problem of reading a barcode became a problem of vision rather than alignment. Software replaced mechanical accuracy. Error correction stopped being a luxury and became a foundation. The scanner no longer asked where the barcode was moving. It asked what the barcode was.

This transition did not happen overnight, and it did not eliminate lasers immediately. Laser scanners remained faster and cheaper for many linear-only environments, and they continue to exist today. But imaging scanners opened a door that lasers could never walk through. They made it possible to read symbols that were dense, compact, rotated, damaged, or two-dimensional.

At that moment, scanning ceased to be a single-purpose device and became a platform. Improvements no longer required new optics, only better software. Decoding algorithms could evolve independently of hardware. New symbologies could be designed without waiting for new scanners to be invented.

By the time cameras began appearing in mobile devices, the foundation was already in place. Phones did not create camera-based scanning. They inherited it. What they changed was scale. A scanner no longer needed to live under a checkout counter or in a warehouse holster. It could live in a pocket.

This is where the barcode’s story quietly turns. Once scanning becomes imaging, and imaging becomes software, the barcode is no longer constrained by how it is read. It is constrained only by how much information it needs to carry and how reliably that information must survive the real world.

And that shift sets the stage for what comes next.

Because once scanners could see, a single line was no longer enough.

VIII. The Rise of 2D Barcodes

Born in Industrial Silence

When two-dimensional barcodes began to appear, they did not arrive as consumer technology. There were no smartphones, no apps, no expectations that everyday people would ever scan anything themselves. 2D barcodes were born in industrial silence, shaped by factories, logistics centers, laboratories, and transportation systems that needed more from barcodes than a single line could offer.

The limitation they were responding to was simple. Linear barcodes could identify an item, but they could not describe it. As supply chains grew more complex, industries needed symbols that could carry serial numbers, batch data, expiration dates, and error correction all at once. They needed codes that could be printed smaller, survive damage, and remain readable even when partially destroyed. This was not about convenience, it was about control.

Encoding Depth Instead of Length

The earliest practical 2D symbologies emerged in environments where scanners were already evolving away from lasers.

PDF417 appeared first in the late 1980s, designed to encode large amounts of data across stacked rows. It found a home in transportation, ticketing, and identification documents, places where data density mattered more than visual simplicity.

Soon after, Data Matrix proved that information could be compressed into remarkably small spaces, making it invaluable for electronics manufacturing and medical devices where space was scarce and traceability was mandatory.

Codes That Required Vision

These symbols would not have been viable without imaging scanners. A laser could not sweep a grid and reconstruct it reliably.

A camera could!

2D barcodes assumed the scanner could see, not just sample. They assumed software could correct perspective, rebuild missing sections, and verify integrity through error correction. The symbol and the scanner evolved together, each enabling the other.

Addition, Not Replacement

It is important to understand what did not happen. 2D barcodes did not replace 1D barcodes.

Retail checkout lanes continued to rely on UPC because it was fast, cheap, and deeply embedded. The rise of 2D codes was additive, not disruptive. They filled gaps that linear barcodes were never meant to address. Identification, tracking, and documentation expanded without breaking the systems that already worked.

In the mid-1990s, QR codes entered the picture, developed for high-speed industrial environments where rapid decoding and robust error correction were essential.

They were engineered for factories, not marketing. Their defining features, fast readability and strong error tolerance, reflected the assumptions of machine vision, not consumer interaction.

At the time, none of these systems were designed with phones in mind. Scanners were still dedicated devices, and cameras were still specialized tools. The idea that a general-purpose camera could decode barcodes at scale was not yet practical, even if the theoretical groundwork had already been laid.

What mattered was that the barcode had escaped the line. Information was no longer constrained to a single dimension. Symbols could grow denser without growing larger. Damage no longer meant failure. The barcode had become resilient, compact, and expressive.

Only later would consumer cameras catch up. When they did, they did not change the nature of 2D barcodes. They simply revealed them to a much larger audience. What factories and hospitals had been using quietly for years suddenly became visible everywhere.

By the end of the twentieth century, the barcode was no longer a label. It was a container. And once information could live inside a symbol rather than beside it, the role of scanning changed permanently.

IX. From Industry to Everyone

The final first steps

By the time two-dimensional barcodes were firmly established in factories, hospitals, and transportation systems, the technology itself was no longer the limiting factor. The symbols worked. Imaging scanners worked. Decoding algorithms worked. What was still missing was scale. Scanning remained an institutional act, performed by trained workers using dedicated hardware, in controlled environments. The barcode had become powerful, but it was still largely invisible to everyday life.

That invisibility was not accidental. For decades, scanning required specialized devices, careful setup, and predictable conditions. Even as 2D barcodes matured, they were designed for systems, not for people. They lived on factory floors, inside warehouses, and on official documents. The idea that ordinary consumers would scan barcodes themselves was neither obvious nor necessary.

The first real cracks in that boundary appeared quietly, and not where most people would later assume. They appeared in Japan, at the turn of the millennium.

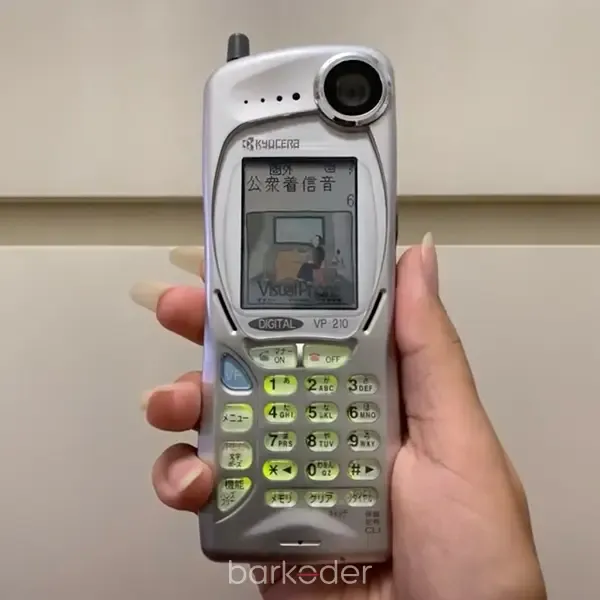

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Japanese mobile phone manufacturers began shipping feature phones equipped with basic cameras, years before smartphones as we understand them today existed. These devices were limited by every modern measure. Screens were small, cameras were low resolution, autofocus was unreliable or nonexistent, and interaction relied on layered menus rather than touch. But for the first time, a general-purpose consumer device could capture an image and process it locally.

QR codes, already established in industrial environments, turned out to be unusually well suited to this moment. Their strong error correction and orientation independence allowed them to survive poor optics and inconsistent lighting. Japanese publishers and service providers began printing QR codes in magazines, posters, tickets, and packaging, linking physical media to mobile services through simple scans. This was not mass adoption, and it was not seamless, but it was unprecedented. Ordinary people could now interact with barcodes using devices they already carried.

Elsewhere, similar experiments emerged more cautiously. Airlines and transit authorities began issuing electronic tickets encoded with barcodes that could be displayed on phones or printed at home. These systems were still tightly controlled and largely institutional, but the interaction had shifted. Scanning was no longer confined to checkout counters or factory gates. It was beginning to enter personal space.

It is important to understand the limits of this phase. Scanning was slow. It required patience, good lighting, and deliberate alignment. There was no expectation of instant recognition, no invisible automation. The barcode did not suddenly become consumer-friendly, but it did become consumer-accessible. That distinction matters.

What changed was not the technology itself, but its role. The barcode stopped being only an internal identifier and started becoming an interface. It offered a way to cross from physical objects into digital systems without keyboards, forms, or manual input. The act of scanning, once hidden inside infrastructure, became visible.

The 2010+

When smartphones later arrived with better cameras, faster processors, and always-on connectivity, they did not invent this interaction. They normalised it. The hardware improved. The software matured. The experience smoothed out. But the conceptual leap had already been made. Scanning had escaped the institution before it ever reached the mass market.

By the early 2010s, scanning felt effortless, even obvious. But that ease was deceptive. It rested on decades of quiet refinement, on symbols designed long before phones could read them, and on early consumer experiments that proved people were willing to scan if the friction was low enough.

What began as a solution to grocery pricing inefficiency had become a universal bridge between the physical and digital worlds. The barcode did not change its nature to survive this transition. It simply waited.

X. When Scanning Became Software

From Device to Behavior

By the time barcode scanning reached consumers through mobile devices, the most important change had already taken place behind the scenes. Scanning was no longer defined by hardware. It was defined by code.

In the early stages of mobile adoption, this shift did not appear as developer tooling. It appeared as consumer-facing experimentation. Companies like Scanbuy, operating through its ScanLife platform, NeoMedia Technologies, and 3GVision with its i-nigma reader were among the first to demonstrate that camera phones could decode barcodes and trigger digital actions. Their focus was not on APIs or libraries, but on behavior. Could people point a phone at a symbol and get something useful in return. Could scanning exist outside institutional systems.

These early efforts were constrained by the devices of their time. Cameras were weak, processing power was limited, and operating systems offered little flexibility. Still, they proved something essential. Barcode decoding no longer required specialized hardware. It could live inside software running on a general-purpose device. The scanner had begun to dissolve into the application.

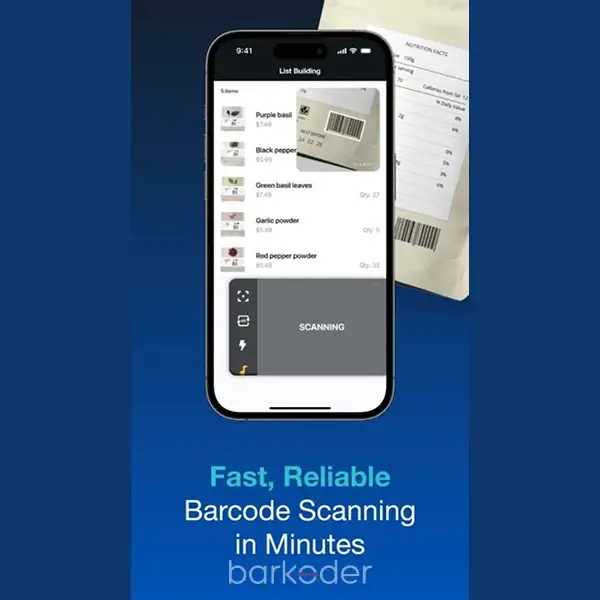

Scanning as a Component

As mobile platforms matured, this idea hardened into something more durable. Developers no longer wanted turnkey consumer apps. They wanted components. They wanted control over user experience, data flow, performance, and supported symbologies. This demand marked a quiet turning point. Scanning stopped being a product and became an ingredient.

One of the clearest signals of this transition was the rise of ZXing, an open-source, multi-format barcode decoding library. ZXing did not sell hardware, services, or campaigns. It offered something simpler and more powerful. A reusable decoding engine that developers could embed directly into their applications. For the first time, barcode scanning became accessible as a shared software foundation, independent of vendor lock-in. The scanner was no longer something you bought. It was something you linked against.

This model set expectations. Developers began to treat scanning as a feature, not a system. Accuracy, speed, lighting tolerance, and format support became software problems rather than hardware constraints. As mobile ecosystems stabilized and commercial demands increased, a new class of companies emerged to meet those expectations.

The Professionalization of Software Scanning

Manatee Works was among the early companies to formalize barcode scanning as a licensable mobile SDK, packaging decoding performance, symbology support, and platform optimization into a product designed explicitly for developers.

Around the same time, Scandit entered the space with a focus on enterprise-grade mobile scanning, emphasizing speed, reliability, and real-world performance under challenging conditions. Cognex, long established in industrial machine vision, extended its expertise into mobile and software-based decoding by acquiring Manatee Works, bringing decades of optical and algorithmic knowledge into the SDK era.

What unified these companies was not branding or market positioning, but architecture. Scanning had become a software problem, solved through libraries, APIs, and continuous algorithmic improvement. Enhancements no longer required new devices or physical upgrades. They could be delivered through updates.

At this stage, barcode scanning returned to its familiar role as infrastructure, but at a new layer of the stack. It lived inside SDKs, embedded invisibly into retail apps, logistics systems, identity workflows, and later augmented reality experiences. Users no longer noticed the act of scanning. Developers no longer needed to reinvent it.

The barcode had completed another transformation. From ink to optics, from optics to images, from images to algorithms. Once scanning became software, it became adaptable in a way hardware never could.

And that adaptability ensured that whatever came next, barcodes would be ready for it.

XI. When Scanning Became Understanding

From Decoding to Interpretation

Once barcode scanning became software, its purpose quietly expanded. The goal was no longer just to read a symbol and return a string of characters. The scanner began to interpret context, to recover information rather than simply extract it, and to understand scenes rather than isolate marks.

This shift did not happen because barcodes changed again. It happened because software did.

Modern scanners learned to tolerate the real world in ways early systems never could. Barcodes could be scratched, partially destroyed, wrinkled, or poorly printed, and still be decoded. Error correction that once lived inside the symbol itself was now reinforced by image analysis, reconstruction algorithms, and probabilistic decoding. A scan no longer failed simply because conditions were imperfect. Failure became something to work around.

Seeing Many, Not One

At the same time, scanners stopped assuming there was only one code worth reading. In warehouses, factories, and retail environments, a single frame might contain dozens of barcodes. Software-based scanners learned to detect and decode multiple symbols simultaneously, prioritizing relevance instead of requiring precise alignment. Scanning became a search problem rather than a targeting problem.

When a Barcode Wasn’t Enough

The definition of a “barcode” also widened. Symbols like VIN codes, stamped into metal or etched onto surfaces, challenged scanners to operate without high contrast or clean edges. MRZ zones on identity documents required structured text recognition, spatial awareness, and strict validation rules. Increasingly, scanners needed to read not just bars and grids, but the text printed around them, extracting serial numbers, lot codes, expiration dates, and human-readable information that complemented the symbol itself.

This convergence blurred the line between barcode decoding and optical character recognition. In many workflows, the barcode alone was not enough. The surrounding text mattered. Software scanners adapted by combining symbology decoding with OCR, treating the entire field of view as a source of information rather than isolating a single mark.

Adapting to the World as It Is

Environmental tolerance became another frontier. Low light, glare, motion blur, curved surfaces, and reflections had once been hard limits. With software-driven pipelines, these conditions became variables to manage. Image enhancement, noise reduction, frame stacking, and adaptive exposure allowed scanners to function in environments that would have defeated earlier generations outright.

As scanners grew more capable, they also became more expressive. In some contexts, decoding a barcode was no longer the end of the interaction, but the beginning. Augmented reality overlays could highlight detected codes, anchor information to physical objects, and guide users visually through complex environments. Scanning evolved from a momentary act into a continuous experience.

What emerged was not a single new feature, but a change in philosophy. Scanning became about understanding, not just reading. The barcode was one signal among many. Software scanners learned to reason about structure, location, confidence, and intent.

In this environment, the barcode stopped being fragile. It could be broken and still meaningful. It could be partial and still useful. It could coexist with text, imagery, and motion without losing relevance. The scanner no longer asked for ideal conditions. It adapted to reality.

This is the quiet culmination of the barcode’s evolution. What began as a way to encode prices had become a general-purpose method for connecting physical artifacts to digital systems, regardless of how imperfect those artifacts might be.

At this point, the question was no longer what barcodes could do. It was how much intelligence could be layered on top of them without breaking the simplicity that made them survive in the first place.

XII. The Quiet Power of a Good Idea

The barcode was never supposed to last this long.

It was created to solve a narrow, almost mundane problem. How to speed up grocery checkout lines. How to reduce pricing errors. How to survive on margins so thin that inefficiency became existential. No one imagined it as a universal interface, a data carrier, or a bridge between physical and digital systems. It was a tool, not a vision.

And yet, it endured.

What separates the barcode from the long list of technologies that promised transformation and then disappeared is not sophistication. It is restraint. From the beginning, the barcode was built on assumptions that favored survival over elegance. It assumed bad printing. It assumed careless handling. It assumed imperfect alignment. It assumed human error. Instead of fighting those realities, it absorbed them.

At every turning point, the barcode avoided the trap of reinvention. When new symbologies emerged, they did not replace the old ones. They surrounded them. When scanners evolved from lasers to cameras, the symbols did not need to change. When scanning became software, the barcode did not demand a new form. It waited. When mobile devices arrived, the barcode did not compete for attention. It adapted quietly.

The barcode succeeded because it respected boundaries. It did not try to be intelligent. It did not try to be expressive. It focused on being reliably interpretable, even when conditions were hostile. Intelligence was layered on top of it, not baked into it. That separation turned out to be its greatest strength.

Over time, the barcode became something rare in technology. Invisible infrastructure. It sits beneath systems without announcing itself. It works across industries without branding. It functions on paper, screens, metal, plastic, and glass. It survives damage, distortion, and neglect. It scales globally without central control. Few technologies manage that transition without collapsing under their own complexity.

Even today, when newer identification methods are proposed, they almost always assume ideal conditions, pristine sensors, and perfect alignment between systems. The barcode does not. It assumes the world is messy and meets it there.

That mindset explains why barcodes were not replaced by newer technologies. It explains why they coexist with them. The barcode never claimed to be the future. It simply refused to become obsolete.

In a world obsessed with disruption, the barcode followed a different path. It evolved without demanding attention. It adapted without breaking compatibility. It waited while everything else rushed forward.

And that patience is why, decades later, the barcode is still here. Still scanning. Still connecting. Still quietly doing the work it was designed to do.

Not because it was perfect, but because it was honest about the world it had to live in.